October 28. Today begins my second week in Vrindaban, and a most auspicious day it is: Anna Kuta, Festival of Grain, a harvest celebration, the most joyous day of Govardhan Puja. This morning, all the temples are decorated with long strips of neern branches and wreaths of mango and tamarind. Flower garlands are strung throughout the temple courtyards. The Deities are dressed in Their best clothes, and huge quantities of food will be offered to Lord Krishna and then freely distributed to everyone. Today, thousands of pilgrims will circumambulate Govardhan Hill.

In Chaitanya Charitamrita, Krishnadas Kaviraj writes:

Of all the devotees, this Govardhan Hill is the best. O my friends, this hill supplies Krishna and Balarama, as well as Their calves, cows, and cowherd friends, with all kinds of necessities: water for drinking, very soft grass, caves, fruits, flowers, and vegetables. In this way, the hill offers respect to the Lord. Being touched by the lotus feet of Krishna and Balarama, Govardhan Hill appears very jubilant.

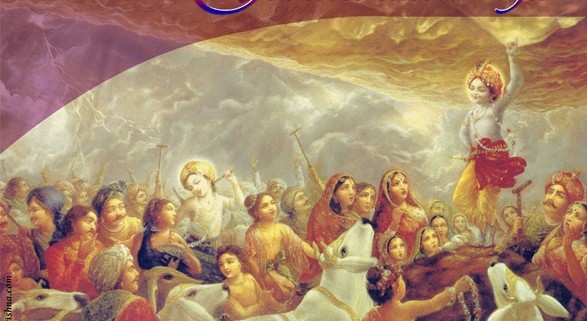

Govardhan Puja was established by Lord Krishna Himself in order to humble the demigod Indra. Being devotees, demigods do not usually forget Krishna’s supremacy, but somehow, as chief of the demigods, Indra had become mad with power. Therefore Krishna decided to rectify him.

The Supreme Lord Krishna ultimately supplies everything to everyone. As long as He’s worshiped, there’s no need to worship the demigods or anyone else. To discourage demigod worship, Krishna argued in various philosophical ways, and the Brijbasis finally agreed to replace the sacrifice to Indra with a harvest festival, called Anna Kuta (anna=grain), in honor of Govardhan Hill and the brahmins.

“Prepare delicious food from all the grains and ghee collected for Indra’s sacrifice,” Krishna told them. “Prepare rice, dhal, halavah, pakora, puri, and milk dishes like sweet rice, sweetballs, sandesh, rasagulla, and laddhu. Then invite all the brahmins to eat their fill. After this, give them some money. Also give sumptuous prasadam to the dog-eaters and untouchables. Then give some to the animals, and give fresh grass to the cows. This Govardhan Puja will satisfy Me very much.”

The Brijbasis, led by Krishna’s foster father, Nanda Maharaj, began to worship Govardhan Hill by chanting Vedic hymns and offering enormous quantities of food. They gave the cows fresh grass, and, keeping the cows in front, began to circumambulate Govardhan Hill. The gopis rode in bullock carts and chanted Krishna’s glories, and the brahmins blessed the cowherd men and their wives. Krishna was pleased to see that all His instructions were being followed. He assumed a great transcendental form and told the Brijbasis, “Govardhan Hill and I are identical.” Then, in the form of Govardhan Hill, He devoured the offered food, and thus favored His devotees.

Of course, this infuriated Indra. He mounted his elephant Airavata and stormed across the sky, leading the dangerous samvartaka clouds. These clouds poured water incessantly, icy winds blew, and lightning flashed. The terrified Brijbasis sought shelter at Lord Krishna’s lotus feet.

“As My devotees, you always depend on My mercy,” Krishna told them. “Now I will save you with My mystic power.”

Krishna picked up Govardhan Hill with one hand, just as a child plucks a mushroom, and held it over all the Brijbasis. like a great umbrella. Thus they were shielded from the torrents of Indra, and Indra himself, being humbled, returned to his abode.

We sit in Srila Prabhupada’s room while he answers letters read to him by Sruta Kirti. It appears that the situation in Bombay will warrant Prabhupada’s personal supervision. The owner of the land in (Bombay) Juhu is stalling. The Society has already given him 50,000 rupees deposit, but he’s claiming that some of his kinsmen oppose the deal. Never before has he mentioned the involvement of other family members. Moreover, the devotees living in the straw huts have fallen sick with malaria.

“What to do?” Prabhupada asks. “As soon as you Western boys and girls come to India, you let yourselves be cheated. Then you get sick. Either stomach sickness or malaria. You don’t know how to take proper care. What can be done? I’m an old man, and now our Society has become too big for me to manage personally. If I’ve committed some offense, it’s that I’ve taken on too many disciples.”

“That’s your compassion, Srila Prabhupada,” Pradyumna says. “You’re too compassionate to let others suffer.”

“It is my Guru Maharaj who is taking care. And he’s under the guidance of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Let us go

to hell, if necessary, but let others be saved. That is the Vaishnava attitude.”

After breakfast prasadam, Achyutananda, two European brahmacharis—Sukadeva das and Vasudeva—and I hire a taxi to Govardhan. By leaving early, we hope to avoid the crowds along the twenty-eight-kilometer road. Srila Prabhupada tells us that instead of walking the whole fourteen-kilometer parikrama—difficult for tender-footed Westerners—we can walk just a little distance around the Govardhan Deities, who reside near the hill on the road between Kusum Sarovar and the town of Govardhan.

“It would be nice to walk the whole parikrama,” he says, “‘but whatever you do, Krishna will appreciate. Just walk the right direction, what do you call—?”

“Clockwise?”

“Yes. You cannot go backwards. When you stop, you must leave the parikrama.”

On the way, we pass only a few pilgrims. The long, flat plain gives no indication of a hill’s existence. Then, just after Kusum Sarovar, we see reddish brown rocks abruptly rising about twenty or thirty feet above the flat expanse. Some cactuses grow between the rocks.

“It’s not very high,” I say. “It looks more like a big quarry than a hill.”

“Every day, the hill sinks into the ground to the measurement of one mustard seed,” Achyutananda replies.

In Braja, it’s not uncommon for great personalities to manifest themselves as hills. Balarama, in the form of Sesha Naga, manifests as Charanpari, Shiva as Nandisvara, and Lord Brahma as Barsana. Millions of years ago, during Satya Yuga, King Dronachal appeared as a mountain in Salmali, eastern India. He had a son, whom he named Govardhan. At Govardhan’s birth, all the demigods showered flowers from the sky. When the sage Pulastya Muni saw Govardhan’s lustrous beauty, he asked for the mountain-son as a gift. King Dronachal, weeping and trembling at the thought of separation from Govardhan, informed the sage that he could never part with him. Pulastya Muni raised his hand to curse the king in anger, but Govardhan suddenly announced that he would follow the sage on one condition: that he be allowed to remain wherever he was set down.

Pulastya Muni agreed and carried Govardhan away in his right hand. As soon as the sage reached Braja, he set Govardhan down and went off to take his evening bath. Govardhan was overjoyed to be in Braja Bhumi. When Pulastya returned and tried to pick him up, he found that Govardhan had become so heavy that he couldn’t be budged. It was then that the sage cursed Govardhan to sink into the ground to the measure of one mustardseed a day. At the time, Govardhan was twenty-four miles high. Today, he’s only eighty feet tall at his highest point. This great sinkage gives some indication of Govardhan’s immense age.

The mountain was transformed at the first Govardhan Puja five thousand years ago. According to the Govinda Lilamrita, Govardhan is shaped like a peacock. This can actually be seen when one consults a map. Radha Kund and Shyama Kund in the northeast indeed serve as the eyes of a gigantic peacock. The tip of its tail is at Punchari. Jatipur—currently the highest point and the place where Krishna stood to lift the hill—lies across from Aniyora, about one-third up the tail. Manasi Ganga is located midway up the body, and Kusum Sarovar is at the heart.

We leave our taxi just past the bathing tank at Kusum Sarovar. Many pilgrims are surprised to see Westerners at Govardhan Puja. They crowd around us, and there’s no shaking them. We walk to a pandal that has a bright yellow canvas roof shading the Govardhan Deity. Sheets are spread on the ground, and pilgrims sit around a harmonium and chant.

When we take off our shoes and enter, all eyes turn our way, but the chanting goes on. We offer dandavats to the Deity, stretching out on the ground and reciting the mantras of obeisances to guru and Saraswati, the goddess of learning.

The Deity is formed from a stone rising out of the hill. Eyes and mouth have been painted on, and clothing draped over Him. Being the embodiment of the hill, the Deity is considered nondifferent from Lord Krishna Himself. We offer some rupees. The pujari, smiling, gives us chanori, those little white sugar balls. The pilgrims seem friendly enough. I take some photos of the Deity, and the pujari requests to get in the picture. Before long, I’m photographing dozens of giggling pilgrims and their wide-eyed kids.

“This is getting out of hand,” I tell Achyutananda. “Tell them I’ve no more film.”

Achyutananda translates, but no one believes him.

“One photo, one photo,” they insist. I detach the flash and pack the camera away. Across the road, a herd of cows passes, led around Govardhan by proud herdsmen. The cows are covered with bright orange sindhur handprints, and spots, and the holy names of Vishnu. Today, they receive extra fodder.

Now the road is crowding up with pilgrims who have finished their morning bath at Manasi Ganga. Govardhan Puja attracts people from all over India. Caste and economic status are irrelevant. Maharajas, goatherds, knife sharpeners, fishermen, untouchables, industrialists, teachers, students, beggars, merchants, mango peelers, incense dippers, garbage pickers, peasant farmers, whatever—all walk barefoot around Govardhan Hill, equal in God’s eyes, members of the world’s largest democracy, Krishna’s immense family.

Today, the maharajas, brahmins, teachers, and other upper class gentlemen are the disadvantaged ones. They survey the ground before walking, trying to avoid pebbles, thorns, and sizzling hot rocks. Others—the barefoot echelons of ricksha-wallas, cowherds, and peasants—walk merrily along, chanting and offering obeisances before the little shrines along the way, bowing down to the ground and touching a particularly holy stone reminding them of Krishna and Balarama.

According to Krishna’s original directions, food is prepared and distributed liberally. Everyone is fed as much as he can eat: raita (chopped cucumber with yoghurt), milk sweets, potato kachoris, samosas, and cauliflower pakoras. Some temples even invite people to sit before plates made of leaves while boys serve big helpings of halavah (farina with sugar, ghee, and nuts), sweet rice, various saffron-flavored sweets—from those purple-flowered saffron fields of Kashmir—dhal soup, rice, chapatis, curried squash, crispy peppery papadams (which look like big potato chips), spinach with curds swimming in ghee, clay cups of watermelon juice and limeade, big white rasagullas (sweet rose-scented cheeseballs that squeak when you bite into them), gulabjamuns, and jelebis, pretzel-shaped sweets of flour, pure sugar, and ghee, congealed on the outside but still hot and liquid inside.

What a variety of physiognomies now crowd the road! The tall, hawk-nosed, mustachioed Rajasthanis lead their families to the parikrama. These were the Rajput warrior clans that controlled northwest India for thousands of years and served as a formidable buffer against the Persians. The men wear turbans—usually pastel colored, sometimes bright orange—and the women wear the traditional mirror-skirts, embroidered and studded with tiny bits of reflecting glass, complemented with big chunky necklaces of jade, ivory, and garnet, enormous silver earrings, and thick silver bracelets and anklets weighing 100-200 grams each.

There are also many Bengalis, golden complexioned, with refined features. The women are dressed in pastel saris and tend to be chubby. Bengali men, lean and handsome, prefer pencil-thin mustaches, in contrast to the Rajasthani soup-strainer. Gujaratis also abound, often identifiable by their stainless-steel, multi-tiered tiffin lunch containers. Since their vegetarian cuisine is the best in India, they bring it along. Even a few Nepalis—short, muscular, round-faced Mongoloids—walk around Govardhan, observing everything with tiny smiles, and giggling when they see us. Yes, what a wonderful celebration is Govardhan Puja!

“So, where should we leave our shoes?” I ask Achyutananda.

“Carry them,” he says.

“Can we trust these kids to watch them?” I ask.

“No.”

“Shoes, shoes, shoes,” one of the kids starts chanting, understanding our dilemma. “One rupee, watching.”

If I lose my shoes, I’ll never find replacements. Size ten is the limit in India. I open the camera kit, take out the camera, and put our shoes inside.

“Photo, photo,” the kids chant, jumping up and down. They follow us to the parikrama, a narrow dirt path through cactus and big red stones.

In my entire life, I’ve never walked very far barefoot, except on a beach. As I start along the path, the kids point at my feet and laugh. Kids the world over are natural sadists.

The parikrama offers no relief. The tiny pebbles are sheer torture.

“I’m not going to last very long,” I tell Achyutananda.

“It’s a long way to Aniyora,” he says.

“No. I mean, I’m not going to make two kilometers. Maybe not even a hundred yards.”

When I try walking, my toes crumple up to relieve the pressure. The body will do anything to avoid pain. Suddenly, I’m holding my foot and stifling a cry of anguish: I’ve stepped on a thorn. It won’t be the last, judging by all the cactus.

The kids laugh as I extricate the thorn. At least I’m amusing someone. But how will I ever get the spiritual benefit of going on the parikrama? The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.

“Go on ahead,” I tell Achyutananda. “I’ll just sit around here and chant japa. Krishna understands.”

“Then I’ll meet you back at the pandal,” he says. “We’ll go into town later.”

Agreeing, I head back.

I offer namaskars to a bearded, long-haired sadhu performing the dandabat parikrama. Between prostrations, he chants Hare Krishna on 108 beads while standing on one leg, one foot placed behind the opposite knee. Then he moves forward one body length and stretches out on the ground. How wonderful to be able to perform such an austerity! I find myself envying him and wishing for such a birth next lifetime.

After putting my shoes back on, I sit on the roadside beside the pandal, chant japa, and wait for Achyutananda.

He returns sooner than expected. Obviously, his feet are killing him.

“Those pebbles are torture,” he says.

“Even old ladies passed us by,” I say. “What’s wrong with us?”

“We’re Yavanas; they’re yogis,” he says.

“And what happened to Sukadeva and Vasudeva?”

“They’re walking a little further, then taking another taxi back. Let’s go into town.”

The same taxi drives us about three kilometers into the town of Govardhan. On the way, we pass the Maharaj of Bharatpur’s summer palace, one of the finest examples of Mathura carving in existence. Today, no artist can be found to carve sandstone lattice windows, peacocks, or any of the other designs adorning the two-hundred-year-old palace and cenotaphs. The art is lost. Still, the buildings stand, neglected yet magnificent.

The town of Govardhan itself is a one-street village centered around Manasi Ganga. Leading to the Manasi Devi Temple are numerous restaurants and scores of pan, cigaret, soda, and chai stands, all catering to pilgrims.

At the entrance to Manasi Ganga, we check in our shoes. Within an open-sided pavilion are the holy bathing tanks, crowded with pilgrims. We push through them to the water, sprinkle a few drops on our head, then push our way back out.

“Actually, we’re supposed to bathe here before going on parikrama,” Achyutananda reminds me.

Outside, we hire another taxi. From the town of Govardhan to the Radha Kund turnoff, we creep along, the taxi’s horn blaring for the people and herds of cows to make way. As they do so, I think of the first Govardhan Puja. Basically, little has changed: Lord Krishna is here, the cows are here, and the Lord’s devotees are here. Thanks to my pampered Western body, I could not walk very far on parikrama, but I feel blessed by just seeing the hill and the great flow of devotion around it.

The enormous tank at Kusum Sarovar is now filled with bathers. We stop for a glass of sugar cane juice mixed with ice and a pinch of lime—delicious and cooling. After Radha Kund, the traffic begins to thin out, and soon we’re racing across the plain to Vrindaban.